The Hostage Experience

Caught in Conflict: 49 Days in Captivity

In 1990, what began as a family sailing trip through the Bazaruto Archipelago became a 49-day nightmare. Dave Muller, his wife Sandy, and their two young children were taken hostage by child soldiers aligned with the RENAMO rebel group during Mozambique’s brutal civil war.

Mozambique Civil War – The Conflict Behind the Capture

From 1977 to 1992, Mozambique was gripped by one of Africa’s most brutal civil wars. What began as a struggle for political power became a devastating proxy conflict between Cold War superpowers. FRELIMO, the ruling party, received support from the USSR, while the opposition group RENAMO was backed by Western and right-wing governments—including the United States, Portugal, and, until 1985, South Africa.

More than one million lives were lost, not just to conflict, but to famine, displacement, and disease. The war tore communities apart, and children were often conscripted into service as soldiers—robbed of their innocence and forced into unimaginable roles.

Not Child’s Play sheds light on this dark chapter in history, as seen through the eyes of one family caught in the crossfire. During their 49-day captivity, the Muller family witnessed both violence and unexpected humanity among their young captors. Many of these children were victims themselves, trapped in cycles of fear and survival.

Psychologist Dr. Neil Boothby later studied what happened to these child soldiers. His landmark case study on post-war Mozambique found that around 60% successfully reintegrated into society—many becoming trusted and productive citizens. His conclusion is as hopeful as it is humbling:

“In the same way an oyster transforms a raw irritant into a valued pearl over time, so too have most of these former child soldiers emerged from violent childhoods to become trusted and productive adult members of their communities and nation.”

Life After Release – Choosing Survival

Despite everything we went through, we survived—and we rebuilt our lives.

Sandy and I were able to resume our careers in South Africa. Our children, Tammy and Seth, returned to school in East London and eventually set off on their own journeys. Today, Seth is a paediatrician in private practice, and Tammy runs a successful consulting business in the UK.

The experience didn’t break us. But it did change us. We made a deliberate choice—to live as survivors, not as victims. That mindset has shaped how we live, how we parent, and how we see the world.

Hope, Strength & Surviving – The Inner Journey

Survival wasn’t just about staying alive—it was about staying whole.

We had no weapons. Our only defence was appeasement, our resources were resilience, humour, and faith. That faith was tested, especially as we struggled with the question that so many others have asked: Why would God allow this to happen?

We were committed Christians before our capture, and you might assume that made things easier. In truth, it made some things harder. I’ve wrestled with those questions for years. Over time, I’ve found my peace—but I also found comfort in the words of those better equipped to answer. One message that helped me tremendously was a sermon by Greg Boyd titled, Does Everything Happen for a Reason?

🔗 Watch and Listen to the sermon here

Even in our darkest days, we never fully lost hope. That hope was strengthened by the kindness we received after our return. Our friends, extended family, our church, and our children’s school communities embraced us with empathy and grace. Their support helped us begin the long process of healing.

And that’s why we now support Hostage International. They fill a critical gap—walking alongside others whose lives have been turned upside down by kidnapping or arbitrary detention.

From Hostage to Hope: My Journey Forward – By Tammy

It always surprises people to meet a hostage survivor. I happen to be one. It is not something you expect. Neither is it something that comes up often in conversation. Having reflected on the subject, I understand that hostage taking or kidnapping is not a crime we have to face up to in most societies. As such, why would anyone ever expect to meet a hostage survivor. Nevertheless, it does happen and sadly, worldwide, it is one of the fastest growing crimes. Let me tell my story.

When we were taken hostage, I was eight years old and my brother, Seth, was five. After our hostage adventure – and I use the word “adventure” with intent, because that’s truly how we children saw it at the time – we returned to normal life, unaware of the full magnitude of what we had just endured.

Life simply carried on. Our friends knew nothing of our experience, and the adults around us treated us no differently. We resumed school, lived active lives, and both became competitive swimmers, representing our province in championships, which took the majority of our time, focus and energy.

By the time we reached high school, our past experience had faded into the background. I was vaguely aware that Dad was trying to write a book about our story, but for us, the world was opening up. We spread our wings—university, careers, independence awaited.

Ironically, it was only when I finally read Dad’s book as an adult, more than thirty years after the event, that I began to truly understand the depth of what my parents had experienced. In a strange way, it stirred a kind of retrospective empathy—a delayed awareness of the trauma we had experienced.

At the time, we were simply too young to grasp the reality. However, with the benefit of age and reflection, Seth and I have come to realise just how easily we could have been trapped in a narrative of victimhood. Only in retrospect can we see how powerfully our parents shaped our perspective—choosing survival over victimhood, resilience over despair. Unconsciously, we absorbed that same mind-set.

While my memories of sailing have dulled with time, I do still hold a few clear memories. I do recall vividly the day before we ran aground and were taken captive. During a fierce storm, Arwen was tossed by the wind as Mom and Dad fought to control the yacht. Seth and I were safely below deck, watching through the portholes as they submerged, fish swimming past like in our own private aquarium. It was strangely magical.

Other fond memories of our time in captivity include simple pleasures such as rolling bicycle wheel rims around the camp with the boys without a care in the world, eating fresh cashew nuts, receiving sugarcane to suck, and fresh paper to draw on. While the experience was undoubtedly traumatic for our parents, we remember it largely as an unusual and exciting time—a testament to how well our parents shielded us from the brutal reality of the war we were trapped in.

Even the missile attacks, the mortar fire, and the near-daily gunshots have faded into curious fragments. Childhood has a way of softening the edges. Seth recalls running around after the shooting collecting bullet shells, blissfully unaware of the danger. I’m told I was frightened and hid during the shootings, but I have no memory of it. What I do remember is the freedom, the novelty, the games.

Laughter filled many of our days—childish, silly moments that still make us smile, though I suspect our parents found some of them rather mortifying and best left unsaid.

What has surprised me is how deeply moved I have felt while reading Not Child’s Play. At times, caught unawares, I have stood at the brink of a sadness I never expected. Recently, Dad discovered a charity called “Hostage International” and reached out to them. They asked for a copy of his book, and Dad asked me to deliver it. As it turned out, I was working just a few kilometres from their office.

That is how I met Georgina, head of communications at Hostage International. She must have sensed something in me needed sharing, because she invited me for a coffee. From that simple meeting, I’ve come to understand how important it is—even for those who think they’re fine and strong —to have someone who will listen with compassion.

From trauma can come growth, and should you choose, the ability to build a life that benefits others. I now feel compelled to give back—to contribute to society in a way that honours the second chance my family was given. That gift is not something that should be taken lightly.

“A powerful summary of the hostage experience.” – Jessica Buchanan, Hostage Survivor

There comes a moment—after the crisis has passed, the dust has settled, and the world has kept turning—when you’re left asking: Now what?

I remember that moment well.

After 93 days in captivity, rescued by SEAL Team VI, the headlines faded. The world called it a miracle. I was “safe.” But inside, I was untethered.

No one tells you how quiet survival can be. How lonely it is to be free but lost.

That’s when the next chapter begins—not with answers, but with questions.

Who am I now?

What do I want?

What’s worth rebuilding?

And maybe the most important one:

What do I choose next?

The truth is, the hardest part isn’t surviving.

It’s deciding how to live after.

If you’re standing in that strange space between the ending and the beginning, let me remind you:

You get the final say.

Not the trauma.

Not the loss.

Not the illness, the heartbreak, or the failure.

You.

Your next chapter is unwritten.

And you’re still holding the pen.

–Hostage survivor, Jessica Buchanan

Table of Contents

Thanks & Acknowledgements

The list of people I need to thank is vast, ranging from the presidents of countries to the lowest ranking seaman on board the SAS Tafelberg. There are many people I know well and people I have never met. I simply cannot thank you all by name, but, if you have read my story, and recognise where you played your part, I hope you will find satisfaction in discovering that, thanks to you, we recovered; even flourished.

When we sailed in the East London harbour, the navy wanted us to stand in the crows-nest of the SAS Tafelberg. That is the highest accessible spot on a ship. They correctly saw us as trophies. I regret it was a role we were unable to play at the time, but more than they could have imagined; we have become your trophies and for that, we are deeply grateful.

There are however some who I would like to mention by name.

- Rusty Evans who kept our families fully informed as Operation Cashmere unfolded and Mr Piet Goosen, who met us on the Tafelberg. Both from the Department of Foreign Affairs.

- Colonel John More who met with Dhlakama in Malawi and negotiated our release.

- As a result of that meeting Captain Marius Ackerman began to monitor, decipher and analyse the radio massages emanating from Frelimo. Thanks to his diligence our time with Renamo was extended, but more importantly, so were the number of days we would come to live.

- Colonel Callie Steijn and Commandant Johan Slabbert who recognised the implications of what Marius discovered and, as a result, Callie unexpectedly found himself in Villanculos monitoring the withdrawal of the Frelimo forces to allow for our rescue.

- Brigadier Wim van der Waals who signed off the execution of Operation Cashmere at the highest military level.

- Captain Bob Harrison who so warmly welcomed us on board his ship and Admiral Massey Hicks who orchestrated the entire operation. We’ve never forgotten that a boat can fit on a ship, but never a ship on a boat!

- The members of RR4 and particularly Col. Alwyn Voster, SSgt. Gavin Christie and Sgt. Pedrito.

- The members of the medical team. Maj. Etienne Kruger, Charl de Wet, Paul van der Walle, Estell Potgieter, Hugo Coetsee. Thank you for hearing our story and for drying our tears.

- Paul Strauss who played a critical role in coordinating the communications between Foreign Affairs and the Navy

- Back home we thank all those who prayed for our safe return. God heard you. In particular thanks must go to the congregation of Cambridge Baptist Church. In this regard, special mention needs to be made of Rev George Dennison who tirelessly provided pastoral support for our families and friends.

- We are grateful to the wider community and particularly the communities of Selborne Pre-Primary and Clarendon Prep schools who accepted our children back without any intrusive questioning.

- I’m grateful to the directors of my practice, Smale and Partners who kept me gainfully employed, despite an extensive period of AWOL.

- Thanks to our sailing friend Otto Kindleman and Judith who provided a safe hiding place for us in the week after our return.

- A very special thanks to a good friend Richard Latimer who over many years, while this manuscript slowly emerged, has been my most enthusiastic and unrelenting supporter and who through his own publications has inspired me to keep going.

- Thanks to Mike Volkman who worked wonders to convert my slide photos to digital format.

Any author is fortunate to fall into the hands of competent editors and publishers. Lauren Smith undertook the first structural edit of this manuscript with all the wisdom and firmness it required. Sean Fraser added the final polish.

I’ve no idea how it happened, but my thanks to the folk at Jacana Media who saw merit in my manuscript and passed it on to a survivor of note, Melinda Ferguson. I appreciate your support and confidence in my story.

And to the person who has sacrificed most. Sandy. No man could have wished for a more loving and strong partner.

Frequently asked questions

Who captured you?

A group of child soldiers from the terrorist group called Renamo captured us.

At the time the socialist aligned Frelimo were fighting a civil war with the western supported Renamo. In effect, this was a proxy war between the east and the west. The war endured from 1977 till 1992. Our rescue required a cease-fire to come into effect. This was the first between the warring parties and provided sufficient trust between the parties to allow peace talks to commence two weeks after our release.

Where were you captured?

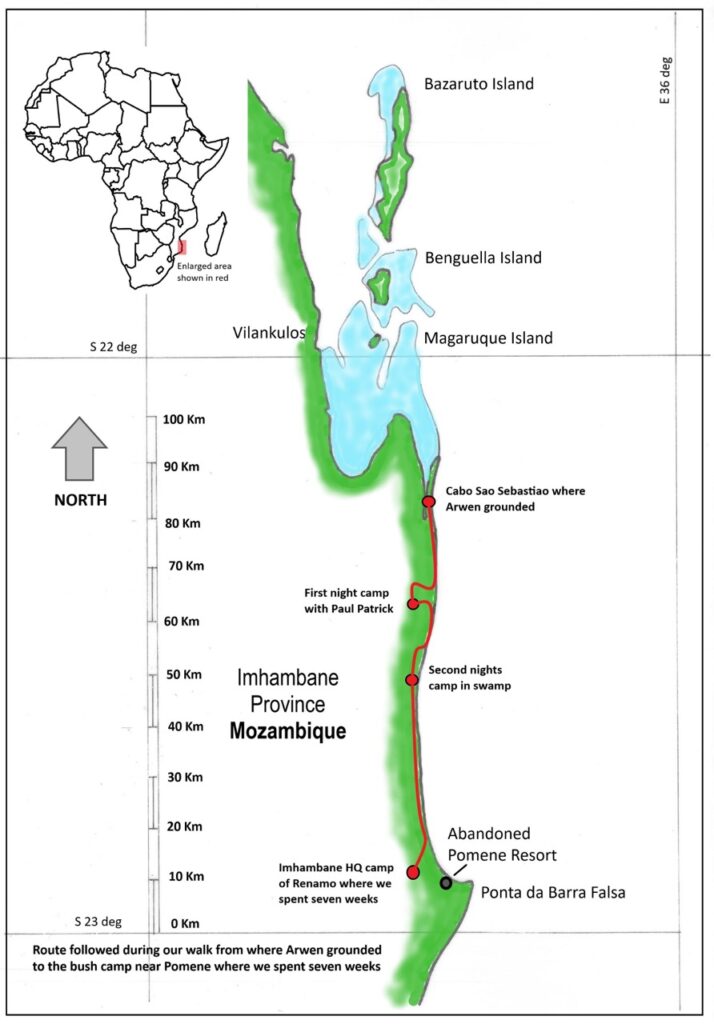

We were captured in central Mozambique, about 30km south of a group of islands called the Bazaruto Archipelago. We were then forced to walk south with our captors for about 70km to an area near Pomene.

Why were you there?

Other than, to gain sailing experience in preparation for a longer voyage, we were sailing to the Bazaruto Islands so that Sandy, my wife and a marine biologist, could investigate the possibility of undertaking future research work on molluscs near the islands. We ran aground in the middle of the night on a sand bar south of the islands and were waiting to refloat our yacht when we were captured by a group of boy soldiers from the Renamo terrorist group.